People who take daytime naps frequently have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and death.Credit: Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto via Getty

Brain benefits from being rocked to sleep

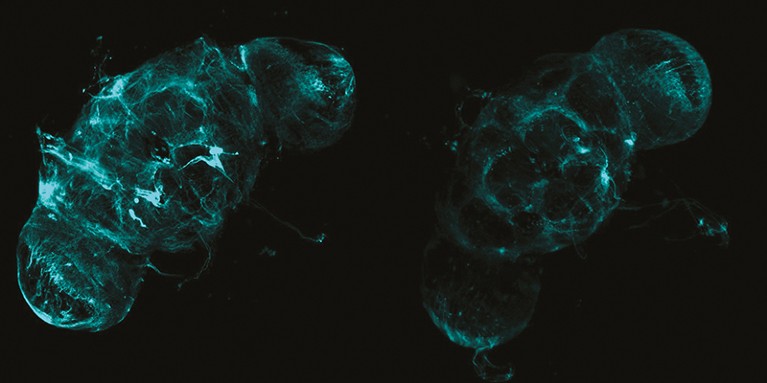

The soporific effects of being gently rocked are well known in humans, mice and even fruit flies that have been specifically engineered to stay awake. Sho Inami and Kyunghee Koh at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, have shown that this vibration-induced sleep has the same beneficial cognitive effects as natural, uninduced sleep.

Researchers used male fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) that had been sleep-deprived owing to the genetically engineered activation of wake-promoting neurons. These flies were placed in vibrating glass tubes for 12 hours per day, and monitored using infrared beams that detected any movement. The researchers first confirmed that the vibration led to the flies sleeping significantly more than flies that weren’t in vibrating tubes but that also had activated wake-promoting neurons. The team then monitored the better-rested flies’ courtship behaviour the next day for signs of benefit.

The team found that those that had been vibrated to sleep showed healthier courtship behaviour than did flies that had not, and therefore had not slept much.

Another group of flies that had been genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer’s disease, which is known to interfere with healthy sleep, were placed in the vibrating tubes for longer stretches of time to see what effect the induced sleep had on disease markers. The researchers found that these flies not only slept better than those who were not vibrated to sleep, but that they also had less accumulation of mutant amyloid-β and tau proteins in the brain, which are hallmarks of the disease.

Nature Outlook: Sleep

The results raise the prospect that the age-old practice of rocking someone to sleep could have clinical benefits in individuals with diseases that reduce sleep quality.

Alcohol increases slow-wave sleep and decreases REM

Around one in five adults in the United States use alcohol to help them get to sleep. Researchers at Brown University and E. P. Bradley Hospital, both in Providence, Rhode Island, found that a pre-sleep tipple delays the onset and decreases the total amount of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, but these effects lessen over consecutive nights of drinking.

One hour before lights out, 30 healthy adults aged 22 to 57 were given a drink that contained either a mixer or a mixer plus alcohol, which was designed to bring them to a blood alcohol level of 0.08 milligrams per litre — around four drinks for the average man. The participants were wired up to polysomnography machines to record their brain activity throughout the night. After three nights, the two groups were swapped over to the opposite drink type for a further three nights.

The study found that alcohol increased the amount of time spent in deep, slow-wave sleep in the first third of the night, but decreased it thereafter. These changes, including a reduction in REM sleep, were evident across all three nights of drinking but most pronounced on the first night. That result suggested a growing tolerance to the effects of alcohol on sleep over multiple days.

Early morning lectures are bad for attendance and grades

A study has confirmed what most students and lecturers have long suspected: early morning lectures are poorly attended, and the few who do attend are so sleep-deprived that no one is learning much anyway.

Given the natural propensity of most university students to go to bed late, researchers at the Duke–NUS Medical School in Singapore and the National University of Singapore speculated that early morning lectures are not only under-attended, but also that students enrolled in courses with more early lectures have lower overall grades.

Researchers used Wi-Fi connection logs for about 23,000 students to reveal that attendance at lectures starting at 8 a.m. was 10 percentage points lower than at those with later start times. By monitoring logins to a learning-management system for more than 39,000 students, and studying the sleep patterns of 181 students, who wore wrist devices to monitor their activity levels, the researchers showed that those who did attend early classes lost an average of one hour’s sleep as a result. The grades of about 34,000 students revealed the academic toll of early lectures: students on courses with three to five early lectures per week had a significantly lower grade-point average than did students who had no early classes.

Nature Hum. Behav. 7, 502–514 (2023)

Naps linked to heart-disease events and death

Daytime sleepiness has long been associated with a range of neurological, endocrine and metabolic conditions, including heart disease, and excessive daytime napping is linked to an increased risk of death.

Although napping is commonly viewed as the purview of the older person, the relationship between napping and disease or mortality risk is complicated by age. Researchers in China set out to investigate the effects of age and gender on this relationship, using data from about 3,000 participants who took part in a multicentre trial called the Sleep Heart Health Study.

Vibration-induced sleep reduced the accumulation of tau proteins (blue), which are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, in fly brains (right) compared with the brains of flies that were not vibrated to sleep (left).Credit: S. Inami & K. Koh Sleep 47, zsae226 (2024)

The team found a significant association between the frequency and duration of daytime naps that a person took and their risk of cardiovascular disease and death. This link was especially apparent in people under the age of 65, and in women aged 65–74. Women of this age who napped more than five times in a week, or for longer than 50 minutes at a time, had significantly higher risk of death from heart disease compared with those who napped less frequently and for shorter times. No such association was seen in individuals aged 75 or older.

The mechanism underpinning these effects is not clear. Excessive napping could reflect inadequate night-time sleep, which could indicate conditions such as obstructive sleep apnoea. However, there are also mechanisms by which daytime naps could themselves influence cardiovascular disease risk.

J. Clin. Sleep Med. 20, 1339–1348 (2024)

Finding treatments for postpartum insomnia

Babies are bad enough for parental sleep without the extra burden of pre-existing insomnia. In an effort to help first-time parents who are struggling with these dual sleep challenges, researchers in Australia and Israel trialled two interventions aimed at reducing postpartum insomnia in 127 individuals who were due to give birth to their first child.

The greatest reduction in both prenatal and postpartum insomnia was seen in people who received therapist-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia, which was delivered over the phone and by e-mail from the start of pregnancy through to three months after the birth. However, a mechanized ‘responsive bassinet’, which plays white noise and rocks back and forth when an infant cries, did not improve participants’ postpartum insomnia. Participants in the control condition received a booklet that explained sleep hygiene.

The authors commented that the findings reinforced the importance of early intervention to tackle postpartum insomnia, and that cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia could help to ameliorate the impact of the condition on new parents.

Light at night increases the risk of mood disorders

A study has found that exposure to too much light when we’re supposed to be asleep is linked to an increased risk of mental illness. Researchers in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom analysed data from almost 87,000 people registered with the UK Biobank study who had completed 7 days of round-the-clock measurements of their light exposure and physical activity, including sleep. They also completed an online mental-health questionnaire.

More from Nature Outlooks

These data revealed that those who were in the top 25% of the group for the brightest night-time light exposure had 30% higher odds of major depressive disorder, 27% higher odds of self-harm, 21% higher odds of psychosis and 23% higher odds of generalized anxiety disorder than did those in the bottom 25%. By contrast, those in the top quartile for daytime light exposure had 19% lower odds of major depressive disorder, 24% lower odds of self-harm and 31% lower odds of psychosis than those in the lowest quartile of daytime light exposure. The associations persisted even after excluding night-shift workers from the analysis, or accounting for other factors such as physical activity and cardiometabolic health.

The study found daytime light exposure could partly attenuate the negative effects of being exposed to light at night. The authors commented that modern humans, unlike our early ancestors, are more exposed to brighter light at night than during the day. Addressing this deviation from natural light and dark cycles might have applications for improving the mental well-being of the general population.