Young researchers in the United States can benefit from the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, which awards students a stipend and pays for their tuition.Credit: Rob Felt, Georgia Tech

Each April, the US National Science Foundation (NSF) offers a cohort of around 2,000 promising young researchers a prestigious fellowship to support their careers in science. Yesterday, the agency, which is a major funder of basic science, announced that it is awarding only 1,000 fellowships — slashing the cohort by half.

‘My career is over’: Columbia University scientists hit hard by Trump team’s cuts

The NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP) selectively offers five-year awards to students pursuing master’s and PhD degrees in the sciences. Only about 16% of the more than 13,000 applicants are usually successful. Fellows receive an annual stipend of US$37,000 plus coverage of their tuition. The GRFP is one of the longest running programmes to fill the global pipeline of science talent: since 1952, it has funded more than 45,000 young researchers. The programme’s goal, according to its website before US President Donald Trump took office, was to “ensure the quality, vitality, and diversity of the scientific and engineering workforce”. A new version of the website replaces “diversity” — a priority the Trump administration has sought to eradicate — with “strength”.

This cut to the GRFP is “a heartbreaker”, says Rob Denton, a biologist at Marian University in Indianapolis, Indiana, who has previously reviewed GRFP applications. Many of the applicants are vulnerable because they’re just starting their careers, he says, and receiving this award “could be the difference between them staying in science or finding another career”.

75% of US scientists who answered Nature poll consider leaving

The cuts to the GRFP add to the headwinds that the Trump administration has been stirring up for young scientists. Under Trump, US funding agencies have been cutting active research grants — many of them training grants for students and postdocs — as it seeks to reduce US government spending. In response to funding uncertainty, some universities have curtailed PhD admissions, and the National Institutes of Health, the world’s largest biomedical research funder, has also cancelled a summer programme for undergraduate students.

The NSF’s ability to administer awards could soon be diminished — a possible reason for slashing the fellowships: The Washington Post reported in March that an internal White House document indicated the agency would soon face a reduction in its staff headcount of 28%. Cutting the GRFP to save money is “boneheaded”, says Kenny Evans, a science-policy specialist at Rice University in Houston, Texas. “GRFPs are one of the most cost-effective ways for NSF to give out money,” he says, because the outcome is a trained, promising young scientist and it’s relatively inexpensive.

An NSF spokesperson declined to comment on the cuts to GRFP, but said that the agency is committed to preserving funding at levels promised to new and existing GRFP awardees. “A subsequent announcement of additional awardees is possible subject to future resourcing considerations,” the spokesperson also noted.

Application ambiguity

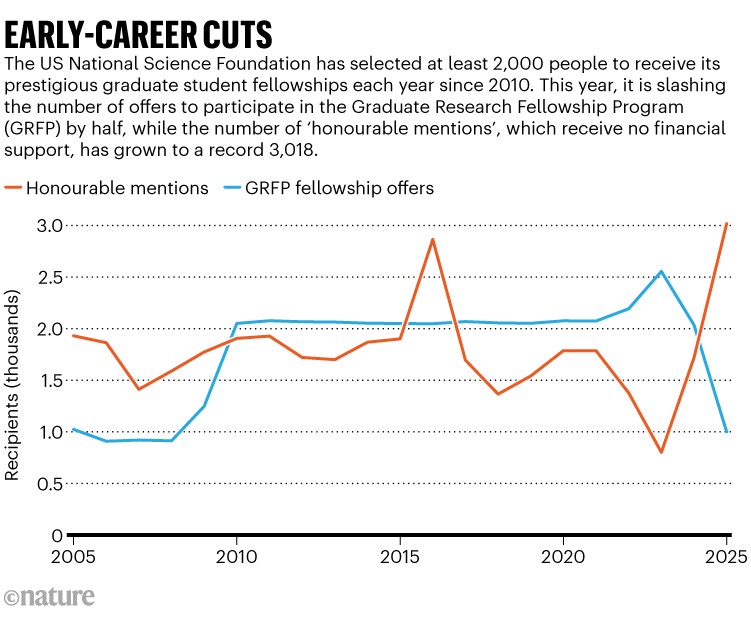

This year’s cuts to the programme mark a sharp decline from a record high 2,555 fellowship offers in 2023. For 15 years, the number of scientists selected for fellowships has remained relatively stable; the last time the NSF gave fewer than 1,000 offers was in 2008 (see ‘Early-career cuts’).

In addition to the 1,000 fellowships, the NSF also named a record 3,018 applicants as honourable mentions — an award that does not provide funding but that young researchers can put on their résumés to boost their standing. The high number of honourable mentions are a sign that there were far more worthy candidates than could be awarded fellowships, Evans says.

Source: NSF