The Matachines ritual dance performed in Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico.Credit: Ernesto Burciaga/Alamy

Members of Picuris Pueblo, an Indigenous American tribe based near Taos, New Mexico, knew they were connected to ancient settlements at Chaco Canyon, 275 kilometres to the west.

Picuris oral histories and artefacts show a link with the archaeological site, a once-thriving centre famous for its ‘great houses’ that was mysteriously abandoned starting around 900 years ago.

Now, an unprecedented collaboration between members of Picuris Pueblo and one of the world’s leading ancient genomics labs has found genetic evidence linking Picuris people to ancient inhabitants of Chaco Canyon.

The study, published1 on 30 April in Nature, offers a model for equitable collaborations between Indigenous communities and scientists. The project was initiated by Picuris Pueblo leaders, who determined how the research was conducted and presented; researchers wishing to use the data generated in the study must get the tribe’s permission.

“I think that’s a big step in the right direction,” says Katrina Claw, a genomicist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, who is Diné, or Navajo, and was not involved with the study.

Craig Quanchello, the Picuris Pueblo lieutenant governor and one of the lead authors of the paper, hopes the study’s conclusions will convince people — including the US government — that his tribe deserves a say in Chaco Canyon’s future. “We’ve always said we have this deep connection to Chaco Canyon,” he said at a press briefing.

A 2023 US government restriction on new oil and gas drilling in the area surrounding Chaco Canyon is facing a legal challenge from the Navajo Nation. A review by the administration of US President Donald Trump is also threatening to repeal the restriction. This month, a federal judge gave two other New Mexico tribes permission to oppose the Navajo lawsuit.

“We steered this ship,” Quanchello said at the briefing, in the hopes that by “using technology in the Western way, that they would now listen”. He added: “We’ve been telling our stories since time immemorial, but this is something on their terms that they can understand.”

The ancient Native American ruins in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, date back more than 1,000 years.Credit: Wil Meinderts/Buiten-beeld/Minden Pictures via Alamy

Ancient remains

The Picuris Pueblo tribe, who number around 300 people, has been working with professional archaeologists since the 1960s. The research focuses on human occupation of the region near Taos since around ad 900. Human remains uncovered during excavations were returned to the tribe in the 1990s, after the passage of a US repatriation law.

In 2018, archaeologists at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas — which has a campus in Taos — identified a set of Picuris Pueblo remains that had been omitted from the repatriation efforts, and informed the tribe.

Hoping to use the remains as evidence of the connection between Picuris and Chaco Canyon, the tribe’s leadership pursued a collaboration with Eske Willerslev, a palaeogenomicist at the University of Copenhagen. His team had previously worked with Native American groups to study ancient human remains, but this was the first time a tribe had sought out his help.

“It wasn’t an easy decision,” Picuris governor Wayne Yazza said at the press briefing. Establishing a genetic connection to Chaco Canyon “was something that we thought would benefit our community”.

After brokering an agreement that gave the Picuris considerable say in the study and control over resulting data, Willerslev and his colleagues sequenced the genomes from the remains of 16 ancient Picuris Pueblo, dating to between 500 and 700 years ago, as well as the genomes of 13 modern tribe members.

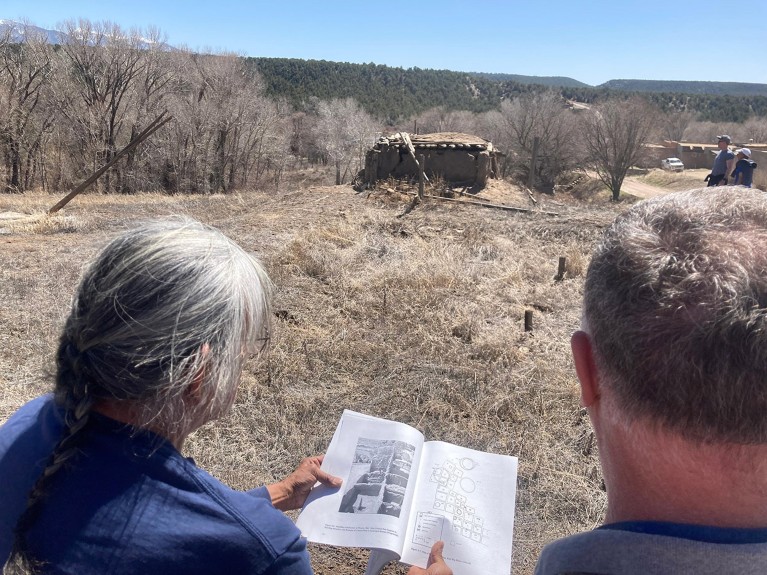

The study was the result of an unprecedented collaboration between members of Picuris Pueblo and one of the world’s leading ancient genomics labs.Credit: Thomaz Pinotti

Comparisons showed a clear genetic connection between ancient and modern Picuris Pueblo people — as well as to ancient inhabitants of Chaco Canyon, whose remains had been sequenced for a controversial 2017 study2. The remains had been stored in a New York City museum and classified as unaffiliated with any tribes. Neither the museum nor the research team behind the 2017 study meaningfully consulted with Native American groups before publication, upsetting many tribes that claim links with Chaco Canyon3.