You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

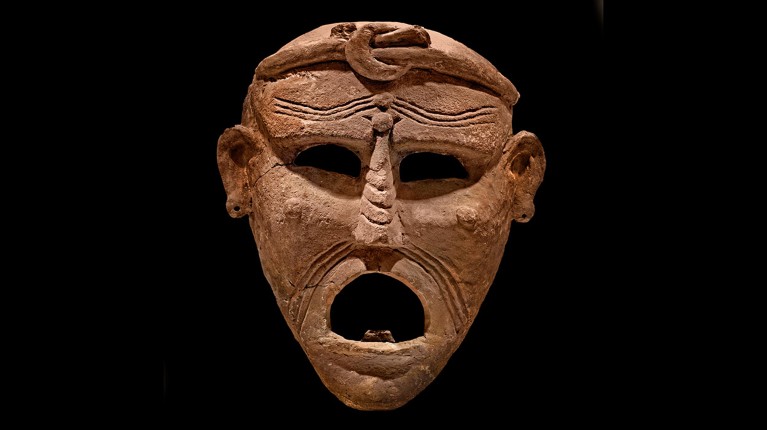

A death mask from the third or second century bc found in the Phoenician trading city of Carthage in what is now Tunisia.Credit: Peter Horree/Alamy

The Phoenicians, an ancient civilization that originated in the Middle East, spread their culture far and wide — but not their DNA. Phoenician city-states across the Mediterranean shared languages, religious practices and maritime trading economies. But an analysis of DNA from the remains of around 200 people from Phoenician archaeological sites reveals that people from Mediterranean outposts of Phoenician culture shared no ancestry with ancient Middle Easterners. Instead, their ancestry profiles resemble those of ancient inhabitants of Greece and Sicily, and North African ancestry entered the mix over time.

Scientists have pinpointed the genes that drive the last three of the seven inherited traits in the garden pea (Pisum sativum) first identified by Gregor Mendel over a century ago. The group sequenced nearly 700 pea genomes, selectively bred pea plants and probed each genome for single base-pair differences in their DNA sequence. They found that a gene that disrupts chlorophyll biosynthesis controls whether a pea pod is green or yellow, identified two genes that help to control pod shape by influencing cell-wall thickness and discovered that a deletion in a final gene can change how the plant’s flowers are clustered.

Rattlesnakes might evolve to produce specialized venoms to target specific prey in competitive environments. Researchers collected venom from 83 rattlesnakes across multiple species on 11 islands uninhabited by humans in the Gulf of California. They expected that on bigger islands with larger snake populations, the vipers’ venom would contain more varied toxins to cast the net of potential prey as wide as possible. Instead, the opposite was true — snakes on bigger islands produced venom with less diverse toxins. This could suggest their lethal bite has been fine-tuned over time to work best on certain prey.

Reference: Evolution paper

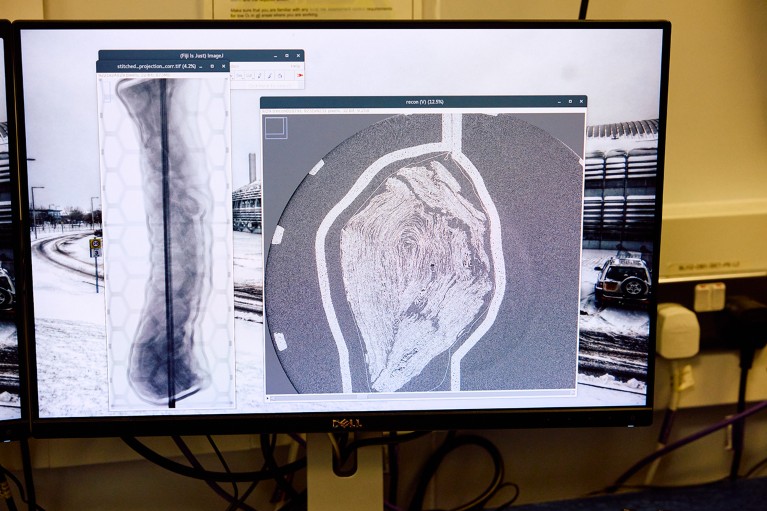

A first look at the newest scans of 18 ancient scrolls burnt in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius reveals that at least 5 of them show what look like clear signs of visible ink. Researchers used the powerful X-rays of the Diamond Light Source, a particle accelerator in the UK, to scan the extremely fragile scrolls at an unprecedented resolution. Signs of ink hint that the contents of the scrolls could be easier to read than previously thought, says computer scientist Stephen Parsons.

A freshly scanned scroll, seen from the control room. The cross section on the right hand side of the screen reveals a complex spiral of rolled-up papyrus. Credit: Emli Bendixen for Nature

The efforts are part of the Vesuvius Challenge, a competition set up to encourage efforts to scan and decipher the contents of the unopened ‘Herculaneum scrolls’ — more than 1,800 carbonized papyri discovered in the eighteenth century among the remains of a luxurious Roman villa.

Features & opinion

With so many programming languages to choose from, which one should scientists learn? Computer scientists and bioinformaticians tell Nature that there are four key questions to help you decide (with plenty of examples):

• What do you mean by ‘programming’? Building software tools and wrangling data need quite different approaches, so start by pinning this down.

• What are your colleagues using? For beginners, it’s good to choose one that a colleague can help with — and if everyone in your field is using a particular language, you probably should, too.

• Which tools are available? ‘Libraries’ extend the core capabilities of programming languages, so you might need to go where the most useful of these already exist.

• How big are your data? If you’ve got gigabytes of genomics data, for example, you’ll need tools that can do heavy lifting.

You could also consider whether a solid community of developers exists in your preferred language, and the cost of licenses to use some programming languages.

After her funding was slashed by the administration of US president Donald Trump, neuroscientist Jessica Cantlon co-founded Science Homecoming, an organization that calls on US scientists to submit opinion pieces to their hometown newspapers making the case for investment in science. In the month since the project was launched, more than 100 articles have been published. “It’s amazing. And they’re from all different fields of science. We’ve even had two Nobel laureates,” says Cantlon. “Bit by bit, our message as scientists is getting through to these smaller communities.”

Researchers have taken inspiration from the principles of origami to develop a new ‘metamaterial’ — a material composed of a system of repeating units designed to exhibit unique properties. The material’s units are made of plastic rods that follow the fold lines of a particular origami pattern. Soft joints between the rods allow the structures to collapse, expand and rotate. As the material is tunable to different applied forces, the team suggest it could be used to make anything from a heat sensor to a collapsible staircase — or, with a little help from a magnetic field, dancing ‘robots’.

Reference: Nature paper

Today I’m celebrating the Hubble Space Telescope’s 35th birthday. Over the past month, NASA have been releasing an iconic image for each year of the craft’s time in orbit. And if that’s not enough Hubble hoopla for you, they’ve also released a free e-book, Hubble’s Beautiful Universe, jam-packed with all of the trusty telescope’s greatest hits.

While I walk down memory lane, why not send us your feedback on this newsletter? Your emails are always welcome at briefing@nature.com.

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma